“When I started using dynamite... I believed in... many things, all of it! Now, I believe only in dynamite.”

The first time I cried in front of my dad was Sergio Leone’s fault.

That’s not quite true of course. I was a kid so I must have cred a lot growing up, but the first distinct memory of becoming visibly upset by art was when I was ten years old.

My dad was an old-school movie guy. John Wayne, Lee Marvin, Clint Eastwood and especially Charles Branson. It meant by default I got to watch a lot of great movies. My mum wasn’t as keen, but he saw no harm in keeping me up til midnight to finish some violent movie where a guy with a face like a brick killed and mutilated 90% of the cast before the credits rolled.

BBC 2 had a brilliantly curated library of movies through the late 1970s and early 80s and when I wasn’t watching black and white classics during the day with my gran I was watching double bills and monthly seasons that ran until the early hours before the station shut done for the evening. So LITTLE WOMEN (1949) in the afternoon and then BREAKHEART PASS (1975) in the evening. Life was grand.

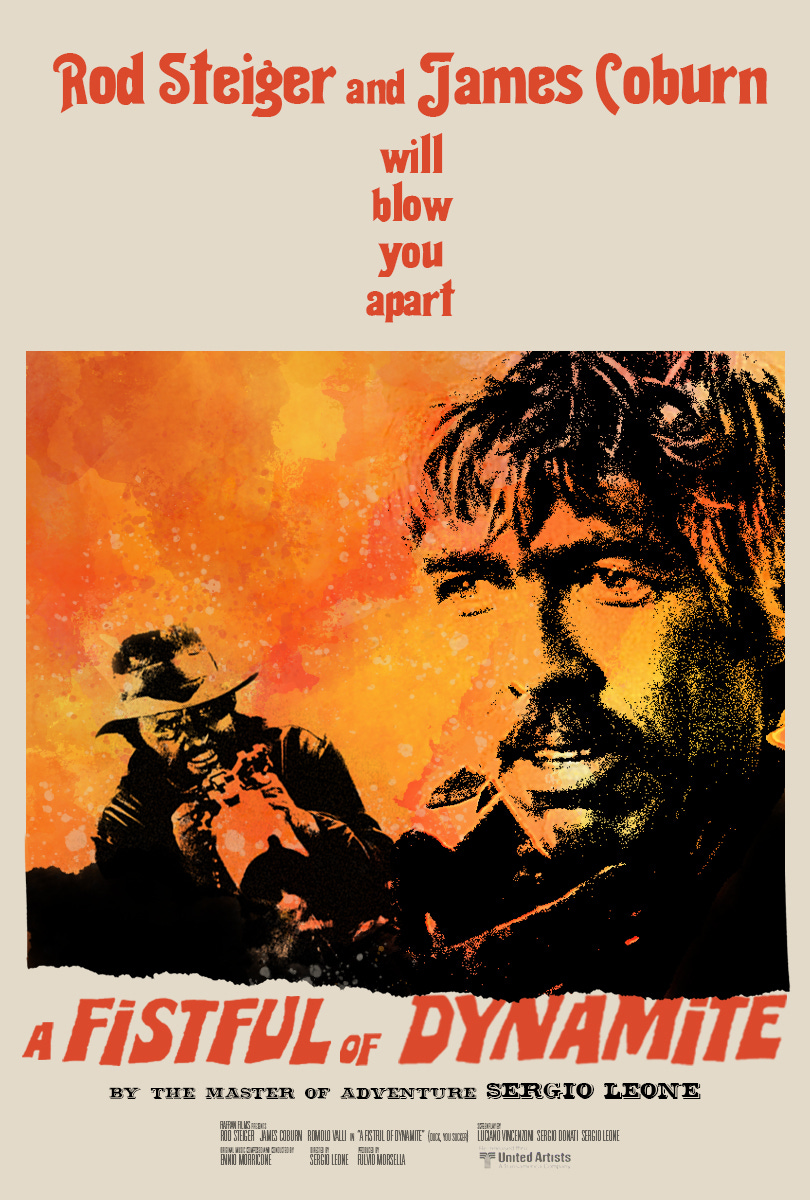

This particular night it was the final movie in a Rod Steiger season that had already introduced me to RUN OF THE ARROW (1957) which I liked a lot so figured another western would be along similar lines.… boy, was I wrong.

The movie we watched aired under the UK title, A FISTFUL OF DYNAMITE (1971), but is equally known as DUCK YOU SUCKER and sometimes ONCE UPON A TIME... THE REVOLUTION. It’s a political western, beautifully shot, very funny, very violent and one that I find profoundly sad. The score by Ennio Morricone is one of my favourites and not only lifts the visuals as all Morricone soundtracks do but also grabs you by the heart and squeezes hard. And it’s a buddy movie with Steiger as a raggedy bandit only concerned with money whose life is changed by an Irish revolutionary played to the hilt by James Coburn. It’s also Leone’s final western.

My dad had already seen the movie and I think Coburn was the main draw for him as he was a big fan of THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN (1960) and the FLINT movies. I was captivated from the very beginning and fell in love with these guys instantly. And then as the movie headed towards its explosive climax it pulled the rug out from under me. Hard.

I remember trying not to cry. I think I was worried about my dad’s reaction, but the movie kept punching me and I lost it enough that my mum, not a fan of westerns, popped her head in the room to see if I was okay.

“He’s fine,” said my dad.

Once the credits rolled I was back in control, but red faced and still wiping at my eyes with the cuff of my pyjamas.

“Time for bed,” he said, and I dutifully headed for the stairs. We had a deal that I could stay up for stuff like this as long as I didn’t fuss when it was time to go up. But then he stopped me at the door.

“Hey, what did you think of it?”

I didn’t have the words. I told him it was good and that I enjoyed it and he replied, “You know if you cry the next time you see this movie despite knowing how it ends then you’ll know its not just a good movie but a great one.”

Huh.

My dad wasn’t much of a talker so this little profound piece of film wisdom has never left me and it became a good marker as the movies I saw over the years began to stack up. My dad’s been dead some 36 years now. The few good, no, great memories I have of us together are all wrapped up in movies. And all this time later I’ve yet to get through a screening of this, my favourite, Sergio Leone movie with a dry eye.

Despite already sending out a newsletter this week I did have every intention of writing a brand new story this evening, but damn it’s hot in London right now and reading back what I started… nope.

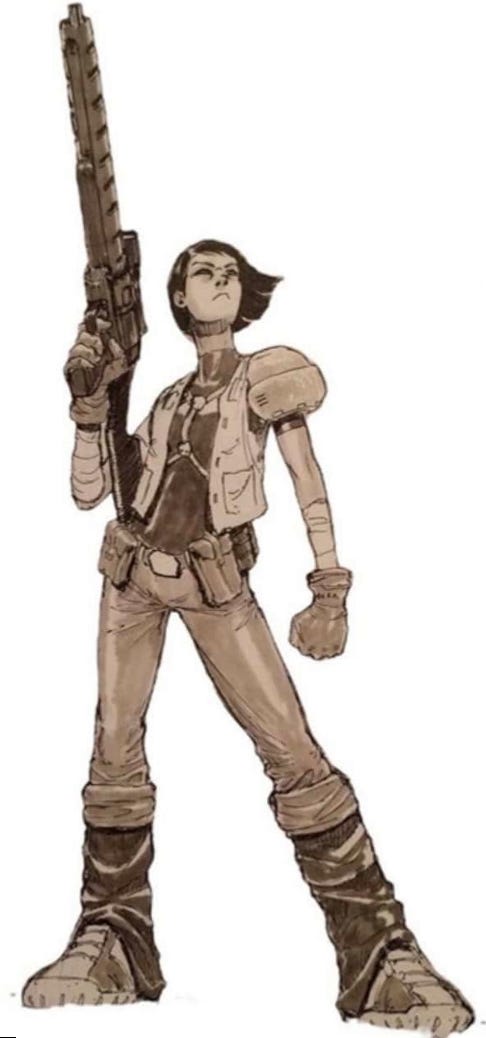

So instead here are two short stories from my Girl & A Gun folder. Some of you will know the first one so apologies, but I don’t think many people have read the second. Normal service will be resumed next week.

Until then all you need is a girl and a gun…

ALL YOU NEED

One

THE GIRL AND THE GUN look down the hill at the man they’re supposed to kill.

The man is dragging a large tree through the snow. Next to him, watching, is a small child.

What date is it today? says the girl.

December 20th, the gun replies.

They watch the two figures until they’re out of sight. It takes a little while. More than enough time for the girl to take the shot.

The gun is confused.

You didn’t take the shot, the gun says.

No, says the girl.

And with that they head back to the airport.

Two

The airport is a mess.

People are rushing this way and that, frantic to get one of the last seats before the Wave hits.

The girl and the gun sit against a wall watching all this.

They have a guaranteed seat on one of the last flights out. Most people don’t.

They watch men with guns—dumb stupid guns, not anything at all like the one the girl holds—try and keep a lid on things.

A man comes over and sits by them. He doesn’t carry a gun. Instead he has a thick notebook and a lot of pens.

Do you mind if I sit here? he asks the girl and the gun.

Why? the girl asks.

The gun wouldn’t have thought to ask this question and is suddenly interested in the answer.

Yes, why? asks the gun.

The man looks at them both.

He’s trying not to look scared, but they both know he is.

My paper is trying to get me on a flight. They told me to stay out of harm’s way. I looked around the airport and next to you seemed to be the safest place, he says.

The gun likes the answer. The man was scared, but he was also smart.

I saw your patch. He points to the one high up on her arm showing a cartoon coyote throttling a cartoon roadrunner.

I was in San Francisco. I saw what your unit tried to do, the man says.

The girl looks down at the patch as if she’d forgotten it was there.

It’s faded, but she remembers the day she got it.

Folds the memory away.

That was a long time ago. But sure. Take a seat, she tells the man.

The man gratefully drops down beside them. He’s smart enough not to ask anything else.

Three

The man wakes up. Something has changed.

It’s quiet now. Most people are sleeping. It’s dark outside.

The girl and the gun are standing over him.

Here, says the girl.

The girl is offering him a sheet of paper.

He takes it and recognizes it at once.

This is your seat, he says.

I don’t need it anymore, says the girl.

He scrambles to his feet as the girl and the gun begin to walk away toward the exit.

Wait. When the Wave hits there’ll be no more planes. You won’t be able to fly out, he calls after them.

She doesn’t turn around.

Four

It’s cold outside.

The gun doesn’t feel it, but registers the drop automatically as it focuses on the girl’s readings via the chip in her chest.

He’s right. How will we get out? the gun asks.

We’ll walk out, replies the girl.

The gun runs the figures, but says nothing.

Five

They reach the foot of the glacier the next morning just as the Wave hits.

The girl and the gun both watch it spread from the horizon.

It turns the crystal blue sky a bright clear green before fading to a new colour that sparkles, lit from beneath by the bright snow and ice and from within by the nano intelligence that just cut them off from the rest of the world.

Now isn’t that something? says the girl.

The gun understands this is a rhetorical question. It tries to lower its sensors anyway so it can experience something akin to what the girl is seeing.

After a few minutes the gun gives up.

You okay? the girl asks.

Yes, says the gun. No effect at all.

Six

They find the first dead body that afternoon.

Nice shot, says the gun.

The girl looks down at the dead man.

The dead man looks at nothing.

Seven

They count sixteen more on the way up. All head shots.

Not far now, says the girl.

Eight

They find them in a half-collapsed tent. Exposed to everything.

You came, says the other gun in the dead woman’s lap.

The girl leans over and gently takes the weapon from the cold hands and examines it.

Are you okay? the girl asks.

Yes. We made contact at 0800 yesterday, begins the other gun.

It’s okay. We’ll take the data. We counted seventeen on the way in. That sound right?

The other gun whirs as it cycles up. Angry.

No. Twenty, says the other gun.

The girl fixes the collapsed part of the tent as best she can.

You did enough for them to have a change of heart, says the girl.

We’ll get them, says her own gun.

This is the first time her gun has spoken since they entered the tent.

She marvels for a moment at how different yet similar their voices sound to her.

Can’t worry about them now. We’ll stay tonight and set off in the morning, the girl says.

She stands and looks down at the older weapon. The same model she trained on.

She folds that away too.

If that’s okay with you, she asks.

The older gun is silent for a moment as it transfers its data over to her weapon.

We’d like that. She said that you’d come. Even with the Wave. She knew, says the other gun.

Nine

The next morning they were some way across the glacier when the other gun detonated its thermite rounds while they were still chambered.

The girl did not look back, but the gun monitored the heat spike until they were too far away for it to register any more.

We could have taken him, said the gun.

Yes, said the girl.

But we didn’t, says the gun.

Would you want to be taken? she asks.

She pauses and looks down at her gun. The sensors along the sight flicker slightly.

No, says the gun.

They walk on in silence for the rest of the day.

Ten

They come upon the men the next morning just as the sun rises into the

broken sky.

They are still trying to carry the wounded one between them. She figures him for the officer.

She drops the man to his right, and then she herself drops to one knee.

They’re too far away to hear the shouting.

They’d ignore it anyway.

The uninjured man runs.

The girl and the gun track the running man.

They ignore the officer who is now sitting upright and firing wildly in their direction.

They’ll want to know why we didn’t kill the man with the tree, the girl says to the gun.

The gun fires and the running man falls face down into the snow.

No. I erased an hour and fifteen minutes from my uploadable memory and logged it as an atmospheric glitch, says the gun.

The girl moves her eye from the scope and down at the weapon in her hands. Two years together and it can still surprise her.

You understand why we walked away? she asks.

He was a low priority. Off the radar for almost a decade and presumed dead. You have operational authority on targets of opportunity, the gun replies.

The officer has stopped firing.

The girl puts her eye back to the scope and watches him bring his sidearm up to his head. She puts a round in his shoulder and moves the scope to watch the weapon fly a satisfying distance across the snow.

Nothing else? the girl asks the gun.

He wasn’t the mission, says the gun.

He wasn’t the mission and the day after tomorrow is Christmas, says the girl.

Eleven

When they get to the officer he’s still alive.

He looks up at them wearily and says something that the girl doesn’t understand.

The girl levels her weapon and shoots him in the face at point blank range.

Twelve

What did he say? she asks the gun.

They’ve been walking an hour.

He said, I killed you. Then he said it again. He thought that we were them, says the gun.

Good, says the girl.

Good.

Thirteen

The man has just set the table when the knock at the door comes.

He looks first to the child still playing with her present in front of the fire and then to his rifle leaning in the frame of the cabin.

He opens the door and looks at the girl and the gun.

We’re sorry to disturb you, but we saw the smoke. We were hoping to rest awhile. We’ll understand if you’d rather we didn’t intrude, says the girl.

The man looks at the girl. The faded uniform. He thinks she’s maybe seventeen. He’s wrong.

We? asks the man.

Merry Christmas, says the gun.

fin

First published in New Military Science Fiction (2014) Apex Publications, LLC

Edited By Jaym Gates & Andrew Liptak.

A Girl and A Gun character design and art by Dave Kennedy.

DAWN CHORUS

One

The girl is asleep when the gun picks up the signal.

It hesitates for a moment before waking her, but only for a moment.

Movement from the town ahead. Lots of movement, the gun says.

She sits up and adjusts her eyes to the gloom. Still dark out. The plan was to walk into the remains of the town at first light. So much for that. She’s awake now.

There’s a signal too. Simple binary. Meaningless without further data.

Let’s check it out.

Two

A long line of refugees are trudging away from the broken walls of the town. The girl and the gun watch them move along slowly. What scant possessions they carry are filthy and seem hardly worth the effort. One old man holds a broken wooden chair with only two legs to his chest, clinging to it like a life preserver.

The girl looks up at the broken sky. Still dark.

I thought this was supposed to be a safe haven, she says.

Maybe something changed, said the gun.

Three

They walk back along the line until they meet a hastily set-up checkpoint. Three soldiers sit around, watching the citizens leave. Two of them, infantry grunts, get to their feet as they spot the girl approach, but the third, a sergeant, continues to roll a cigarette. He’s older than the other two by a decade at least.

What’s the problem? the girl asks.

Road’s closed ’til tomorrow. Sapper went rogue and now we’re waiting on air support to take it out. Evac in full effect until we get the all clear.

The girl looks up at the first hint of a glow on the horizon.

Can’t wait that long. Where’s the Sapper?

One of the grunts, recognising her equipment, takes a step back.

Sarge…

Stow it, Dainty. Sounds like the lady is planning on solving the problem for us.

He still hasn’t looked up, but now taps the radio at his collar. A burst of static and then machine language fills the air. There’s a rhythm to the broadcast then static again before it repeats.

Damn thing’s been jamming local comms with that crap for the last hour. Every time we try and get close it levels another building. And some idiot decided to armour the damn thing so our orders are to fall back and let Air Cav do its job before the damn thing takes out the other half of the town. So the road is closed unless you fancy wandering in there all alone.

Bringing the cigarette to his lips he finally looks up at the girl just as the sun begins to rise behind her.

She’s young. No helmet. Hair tied back in a loose ponytail. Small backpack. Her distinctive red collar matches the red piping on the edge of the military jacket she wears. It’s dusty and worn in places, but clean. He takes in the patch on her shoulder and the cigarette falls from his mouth.

On her breast pocket, where he’d expect to read a name, is a white on black symbol that could be a B or a 13.

Eyes wide with surprise he knows its neither.

In her arms she carries what looks like a rifle. It’s not. The hollows in its barrel match the red details of her uniform and a sensor embedded in the forestock pulses softly when it speaks.

She’s not alone, says the gun.

Four

Twenty minutes later she’s overlooking what used to be a street with the sergeant at her side. Below them a blur of yellow straight edges and glistening silver metal is pummelling a wall to dust.

Sapper, the sergeant explains redundantly. Our variation on construction exo-skeletons, but twice the size as the human element is significantly reduced. Handy to have ’em cleaning up behind you, but tricky to take out when they have a mind of their own.

The body is a dull green over faded yellow, but both fists are exposed, scarred chrome. The right one, a modified jackhammer, beats the remaining structure down into the road as if to make the sergeant’s point for him.

As the sound of the collapsing building fades, the Sapper stands, allowing a view of the dull marks from small arms fire that scar its back. It looks towards a single low building that was hidden behind the now destroyed block.

It’s a school, says the girl.

Don’t worry, says the sergeant. Area’s evacuated and that building hasn’t been used by children in years.

The Sapper turns its head towards the sun and suddenly the machine code is in the air, playing from somewhere deep in the machine’s chest unit. The sergeant’s radio begins too squark the same noise before he turns it off in disgust. But elsewhere the call is heard and taken up by civilian radios through shattered windows and empty cars.

A cacophony of machine singing that fills the broken town.

A regular dawn chorus, marvels the sergeant mockingly.

It’s a standard non-combat unit normally deployed to blow and build bridges or take down unstable structures, the gun says. Dumb as dirt processor. Probable glitch in the organics.

Organics? asks the girl as she watches the Sapper begin to walk slowly towards the school.

Why waste high functioning positron networks when its cheaper and easier to wetware a cadaver? replies the gun.

Ick, says the girl. How do I stop it?

I can punch through the armour if you can get us in a little closer.

Wouldn’t recommend that, begins the sergeant.

Fall back, Sarge, says the girl.

He does as he’s told.

Five

The girl stands and fires.

The round PINGS off the Sapper’s head.

Got its attention, says the gun.

In a blur the machine charges their building and suddenly the girl is riding a wave of rubble down towards her target.

The Sapper is already turning back to the school, ignoring the masonry collapsing around it as the girl lands on its back and swings a leg over its shoulder.

The non pile-driver arm raises and the giant fist comes up to meet her as she pushes the gun below and under the Sapper’s faceplate, pulling the trigger to blow the back of its head out.

Blood mixes with oil as the giant hand clutches at the damaged area and falls to one knee.

The girl and the gun, thrown clear, watch as the machine crawls towards the brightly coloured building.

This thing really hates schools, says the girl.

She casually hops up on its back and walks towards the large exit wound.

The machine carries them to the edge of the school where its hand reaches out and shatters a large window. The town behind them has fallen silent now, but they can still hear the low growl of machine language above the sound of straining gears and falling glass.

This feels weird, the gun says as she lowers it into the torn metal and takes a bead on the pink matter held together between four wetware plates.

PHUT.

The gun destroys the brain with a single shot. The machine stops moving. Falls silent.

Putting a human brain into one of these things, weird? Sure.

She walks away from the dead machine and looks at the path of destruction its wreaked through this quarter of the town. A more or less straight line of demolished buildings and overturned vehicles.

Weird that it was heading for this building in particular I mean, explains the gun.

The girl pauses to pull her backpack from the rubble.

This was just the next building in its path. What the hell would a demolition mech want with a school?

The machine code plays from the gun once. She looks down at the rifle in her hand curiously. What was it saying?

01001011 01010100, says the gun.

They move around the Sapper and past the shattered school window.

Binary? asks the girl.

Same two letters over and over, says the gun.

As they walk away they don’t see the cluster of brightly painted paper caught by the breeze flutter amongst the broken glass, splattered oil and blood. One piece unfurls and lands against the cold metal of the Sapper’s cold hand.

A child’s drawing of a smiling crayon family. A cartoon girl and adult in matching dresses hold hands while a third figure hovers above them on crude angel wings. Printed in a slightly messy but legible scrawl are the words MOMMY, DADDY and ME next to each character.

It’s signed at the bottom; KATIE ANDERSON, AGED 7.

KT, says the gun.

Just that. KT. KT. KT. Over and over and over again.

K.T.

The sun climbs into the broken sky.

They follow it.

fin

I frickin’ love these characters! Similar idea to the Slingers gun in the sense that you took that idea, added more personality (that we may not have had the chance to see in the sizzle reel), and built an inanimate object into a character with which we build empathy. Nice job! 😎